The real-life inspiration for this Diablo IV art

Game art is a genre unto itself—but sometimes it takes more than a little inspiration from the fine art hanging in your favorite museum.

There’s game art, and then there’s game art.

Browsing through the visuals for Blizzard’s new action role-playing game Diablo IV, I felt like something different was on display. Sure, the character studies are incredibly detailed. Yes, the landscapes and environments are wonderfully immersive. Absolutely the objects and textures are more vivid than ever before.

But what’s the deal with those paintings?

And why do they look sort of…familiar?

Igor Sidorenko, a principal concept artist for Blizzard, is the artist responsible for a small collection of Diablo IV art that seemingly draws inspiration from fine art hanging in some of the world’s greatest museums. In a world that’s constantly asking if game art is fine art (with apologies to the late Roger Ebert, we argue yes), Sidorenko’s illustrations felt like a winking rejoinder to the question.

I asked Sidorenko to walk me through the thinking and inspiration for these pieces. Here’s what he said.

Your illustrations captured my attention because they looked less like "game art"—hyperreal, perfect, larger than life—and more like fine art in a museum. What was the goal of this direction? Why?

Our art director John Mueller was quite vocal about it. In pre-production, we establish the pillars and core ideas of the visual language we intended to pursue in pre-production. It was clear then that creating rich, gothic imagery was an important goal. We wanted to move away from high fantasy art—saturated, exaggerated—and get back to the dark roots of the Diablo series, to ground it.

So the vision was, let’s make Diablo a painting and connect it with traditional fine art like drawings and paintings. Let’s take the inspiration from academic art, neoclassicism, pre-Raphaelites and their followers, from pieces like “The Last Day of Pompeii” or “The Raft of the Medusa,” and insert it into the decaying, brutal world of Sanctuary. So we started working in this direction from the very beginning to make it clear for a public, when people can finally see it, that this project is going to be different.

Some of these evoke large-format French paintings, e.g. Delacroix or David. Some look like Rodin sculptures. Some seem to evoke religious art. Others seem to reference baroque battle scenes. And yet there are still clear fantasy references in this: Thor, Conan the Barbarian, et cetera.

It’s not easy to talk about these pieces collectively. Lots of time passed between each piece, my visual preferences evolved, my painting techniques evolved. I didn’t want to stay within certain style anyway. I wanted to explore as much as I could to create variety and reflect different periods of art history.

Modern art history spans hundreds of years and many thousands of works by people who dedicated their lives to art. To recreate it is a goal beyond the realm of what’s reasonable, obviously. So all we could hope was to deliver something that would make people think about a classic tradition behind it. And, of course, pay homage to what we love.

Let’s talk about some of these pieces.

Sure. The big battle scene above was heavily inspired by Gyula Benczúr’s “The Recapture of Buda Castle in 1686” and Jan Matejko’s “Battle of Grunwald.” We wanted to have a “last stand” scene—a battle filled with chaos, anger, and desperation.

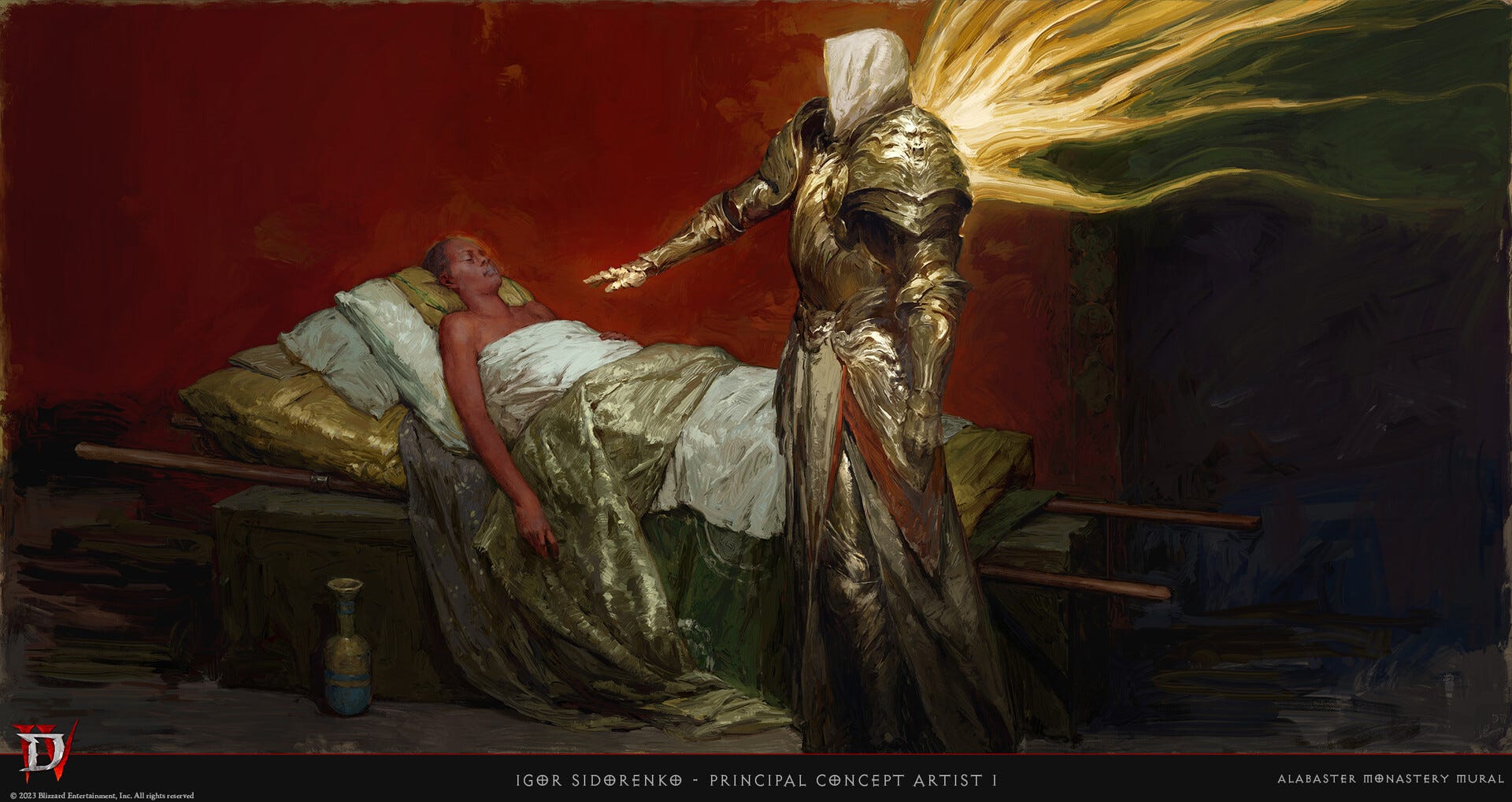

Murals for Alabaster Monastery (above, below, and top of page) are my favorite ones. I wanted to have a strong religious feel here: The moment of creation (Genesis), the revelation of deity (Revelation), the ascension of Jesus into heaven (Ascension). Fortunately there is no shortage of European paintings based on biblical stories in any period.

Above, I was mostly inspired by Benczúr’s masterpiece “The Baptism of Vajk” as well as different artworks by Edwin Austin Abbey and Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant.

There isn’t a specific piece of inspiration for the above, but it is probably the best example of the dark gothic vibe we were looking for—trying to recreate something reminiscent of grim cathedral arch reliefs and gargoyles.

It was fun to work on the above reliefs, too. I love late 19th century art, pre-Raphaelites, and classic American illustration. These were particularly inspired by paintings and drawings relating to the mythology of King Arthur, Norse and Germanic myths, Celtic sagas, et cetera—which I am very fond of. And again, there were plenty of beautiful pieces to be inspired by: Alphonse Mucha’s “The Slav Epic”, Abbey’s “King Lear,” and different works by Arthur Hacker and John Singer Sargent.